Features

Golf at the 1904 Olympics and the story of George Lyon

By Brendan Gallagher

By Brendan Gallagher

I’m taking a modest punt here, but I would be surprised if the newly crowned men’s Olympic golf champion at the Reserva de Marapendi course in August was to make his way to the podium by somersaulting into a handstand and walking on his hands to raucous applause.

That’s how George Lyon celebrated when he won the title at St Louis in 1904, but then again the muscular Canadian was a very singular man. For a start he was an old dog of 46 in a field of young pups and on the subject of age it’s a sobering thought that Lyon’s Scottish grandfather, also George Lyon, fought against Napoleon in the Peninsular Wars in 1812.

Lyon was a considerable all-round sportsman who managed to avoid golf until the age of 37. As a young man he set a Canadian pole-vault record, excelled at baseball and then went on to captain the Canada cricket team with a highest score, at club level, of 234. In the winters he played ice hockey and curling. Frankly the prospect of shuffling around a golf course appalled Lyon, but the Toronto insurance salesman experienced a very specific Damascus moment.

He was waiting for cricketing pals to turn up for practice on the evening of October 15, 1895, when a work acquaintance, John Dick, playing golf on the adjoining Rosedale club, called over a hedge and persuaded the reluctant Lyon to try a few shots. Lyon ‘set-up’ as if taking a middle-stump guard when facing a quick bowler, but with his natural eye and sense of timing immediately started to make meaningful contact and was hooked good and proper.

Lyon never did alter his technique hugely – even at the height of his success his swing was described as that of a “coal heaver” – but his innate hand-eye co-ordination coupled with an athletic robustness quickly led to success. By 1898 he was the Canadian Amateur champion, a title that he was to win on eight occasions, the last at the age of 56.

Not being a man of independent wealth, Lyon profited greatly from the patronage of wealthy local businessman and golf fanatic Albert Austin, who pointed him in the direction of the 1904 Olympics.

At which point a diversion into Games history is required. The first modern Olympics in 1896 was a notable success but the money men and entrepreneurs soon moved in and the 1900 Olympics in Paris became nothing more than a sideshow to the six-month-long Exposition Universelle, which was being staged to commemorate mankind’s achievements in the previous century.

There was in fact a small golf competition – featuring men and women at the Compiègne club – that received little publicity with nobody sure whether it was an Olympic event. No medals were issued, which rather promoted the idea that it wasn’t but its Olympic status was retrospectively confirmed by the IOC.

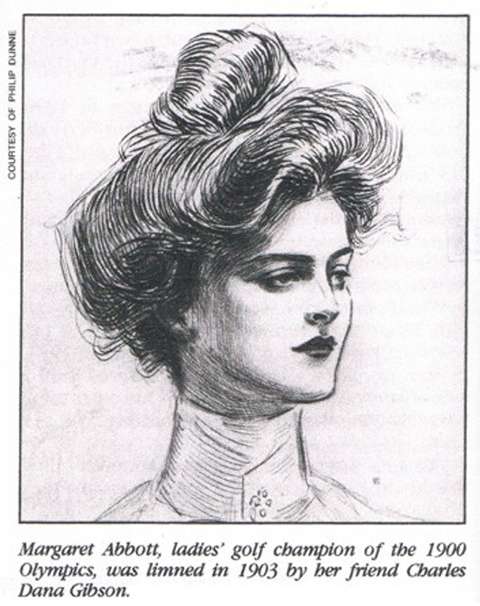

Charles Sands, of the USA, won the men’s event, shooting 82 and 85 to beat Walter Rutherford, from Jedburgh, by one stroke with another Scot, David Robertson, a rugby international, in third place. In the women’s event, Margaret Abbott, an American studying art and sculpture under Rodin in Paris, won the nine-hole competition with a score of 47. Her mother Mary was seventh, to this day the only instance of a mother and daughter competing against each other at the Olympics.

Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the modern Games, was embarrassed by the shambles that was Paris 1900, but had high hopes of a stand-alone Games in Chicago in 1904. The politicians and money men got involved again, however, and it was switched to St Louis, which was hosting the extraordinary World Fair of 1904.

Yet again the Olympics were consumed by the bigger event. No less than 19,694,855 spectators paid their 25 cents admission fee to attend the Fair. In that sea of humanity, attendances at the Olympic sports events were a drop in the ocean, perhaps 3,000 for the week-long golf competition.

De Coubertin pointedly boycotted the 1904 Olympics in disgust and possibly at his behest neither Britain nor France sent teams, although GB did officially win one gold. Irishman Tom Kiely from Co Tipperary, the world’s greatest all-round athlete of the time, won the decathlon but because Ireland was not independent he was forced to register as a GB athlete.

For golf, the absence of the Brits was a major blow. Lyon had expected to compete against the likes of the legendary John Ball, Harold Hilton, Robert Maxwell, Charles Hutchings and Horace Hutchinson.

That disappointment was compounded when another major contender, Walter Travis, the Australian who became a naturalised American, withdrew for unexplained business reasons.

In their collective absence the man to beat was undoubtedly Chandler Egan, 20, who has stormed to victory at the USA Amateur Championship the previous week. Egan was long for the time, quick-witted and a very hot putter when in the mood. He was a thoroughbred but the peculiar tournament set-up also placed an emphasis on rock-solid stayers. Men of substance and stamina.

The 75 participants – paying a $5 entry fee apiece – would play 36 holes medalplay on the Monday with the top 32 then progressing via rounds of 36 holes of matchplay. Given that in those gentlemanly days the pairings often played until the final hole even if the match had been won that amounted to 216 holes of competition golf in six days. Just to up the ante, it hosed down all week, regularly blew a gale and the hilly 6,000-yard course became muddy and sodden.

Perfect conditions, however, for the rugged Canadian who qualified comfortably for the final 32 with an aggregate of 169 before matchplay victories over John Cady and local hotshots Stuart Stickney and Albert Lambert. Lyon recorded a ‘course record’ of 79 in beating Stickney 11&9 but was pushed to his limit in the semi-final finishing one up after 36 holes against Francis Newton from Seattle.

Which teed up the final against Egan, played in Biblical conditions. Lyon seized the initiative by winning four of the first five holes and spooked his younger opponent by consistently outdriving him. Egan had won the long-drive competition the previous Saturday, when Lyon was still in transit from Toronto, and, trailing behind, pricked the delicate ego of the super-confident Chandler.

The Harvard student did start to get hot with his putter later in the day to apply a little pressure but it was to no avail as Lyon kept his nerve to win 3&2. The two met once more in their careers, in the second round the US Amateur two years later when Lyon won at the second extra hole, the year when he finished runner-up overall.

You could argue that Lyon won two Olympic gold medals. He travelled to Britain expecting to defend his title in 1908 and a competition had been arranged based at Royal St George’s, Princes and the Royal Cinque Ports. Indeed in the official IOC report of the 1908 Games there is a 16-page section outlining how the tournament would be run, the schedule and the rules.

However, somehow the R&A got into dispute with the BOC and IOC over eligibility and, it would seem, exactly which rules would apply. Whatever the situation – and in all honesty golf had been little more than lukewarm to the entire Olympic ideal – the tournament was cancelled at the last minute.

The organisers wanted to award Lyon the gold medal but the Canadian took a rather Olympian view of such squabbling and chaos and pointedly declined the offer.

Tagged George Lyon, Olympics