Featured

Paul Mahoney: How I nearly decapitated Arnold Palmer at Bay Hill!

Arnold Palmer turned 86 last week. He’s lucky to be alive. Ten years ago, I nearly killed him. Six inches to the left and I would have knocked his block off. I sent a thinned wedge shot soaring across the 1st green at Bay Hill where Arnie was watching leaning on his putter. The horror unveiling before my eyes turned the scene into one of those slow motions in the movies as the camera traces the bullet flying towards its target. There was no time to shout at Arnie. Whizz went the ball zooming at the head of the King.

It had taken about two years of emails before I got the call from Palmer’s office that my request had been granted to play golf with Arnie for a story in Golf World magazine. So here I was, the assassin. Frankly, it was his own fault. He had put himself in harm’s way. What did he think was going to happen when a nerve-racked 18-handicapper whose stomach was churning like a spin dryer had to play a chip over a bunker from a hardpan lie in front of golfing royalty?

That, at least, was going be my first line of defence in the inevitable murder trial. Time stood still. Luckily, so did Palmer. Had he moved just one step to the left, he’d have been a goner. The ball and the life of the seven-time Major champion flashed before his eyes. Unfortunately for the lawyers, the ball blazed past the King and dived into a bush. Having only played three shots, the thought occurred to me that I would now have to take the walk of shame and search for the offending missile. But Palmer had seen enough. His life had been spared. In return, he decided to spare me any more shame. “We’ll give that ball a rest, Paul,” he said in his gentle American twang. What he was saying to himself inside his head in colourful Anglo-Saxon would not have been repeatable.

It took until the sixth hole before I could even look Arnie in the eye let alone strike up a conversation. He still bought me a beer, though. Three, actually. He wouldn’t let me pay for anything. I sat around a table in the bar with him and his mates and we trash-talked the round. But Palmer didn’t mention The Incident once. Neither did anyone else. But it hovered in the air. I was the elephant in the room as well as on the golf course.

The day in the company of the King was like a dream. Daft things that only happen in dreams kept happening – as well as the nightmare scene. We played in a six-ball with no handicaps allowed and no limit on the amount of clubs in your bag. Palmer had at least a dozen drivers and too many putters to count in two bags. It was $50 each into the pot, best score to count. I played in Arnie’s team. There were four other teams. I was hopeless. We won. I took home $200. I felt ashamed.

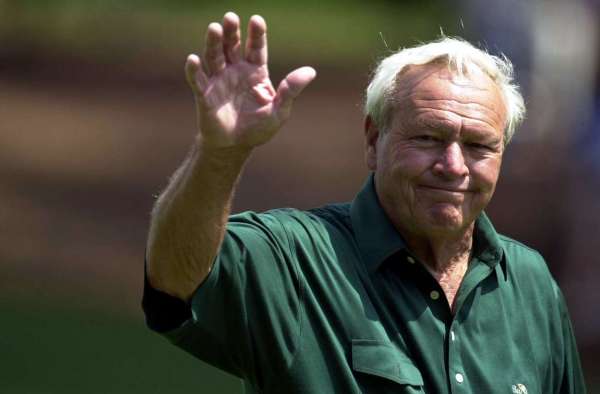

Farewell: Arnold Palmer waves to the crowd at the end of the US Open round at Oakmont in 1994 (photo by Getty Images)

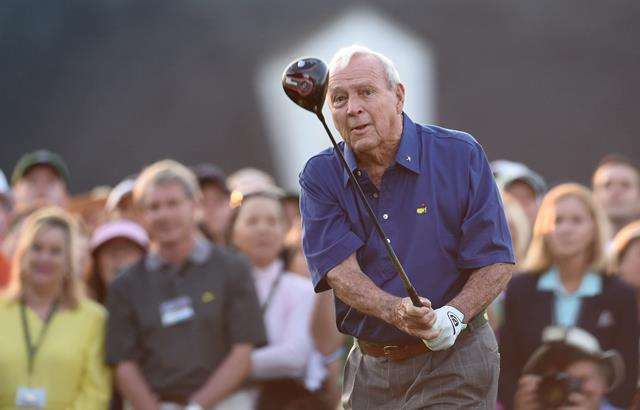

The weirdest scene, besides the assassination attempt, was when Palmer walked out of the clubhouse and headed to the practice range to warm up. There were golfers everywhere, chipping, putting, whacking balls – a busy golf club full with members and visitors. Arnie appeared. Everyone stopped. Everyone just stared at him smacking balls with that trademark style of a caveman lunging at a pterodactyl with a club twirl to finish like a kid signing an autograph in the air with a sparkler.

“This happens every time he comes out to play,” an assistant pro said. Palmer must know that all eyes are on him all the time when he’s in his Bay Hill kingdom. The pressure must feel suffocating. I mention this peculiar scene to him. “I’m used to it,” he said with that boyish smile. “It’s been like that most of my life. I really don’t mind.”

Palmer simply loves people as much as people love Palmer. No one bothered him for an autograph on the course, but I watched him wandering off to his lodge after we had supped our beers. A dozen visitors approached him. He stopped, chatted, signed hats and gave everyone his customary thumbs-up. No bodyguards, no entourage. Just the King and his people.

They say you should never meet your heroes. They never met Arnold Palmer. He made me feel like a mate, one of his gang. He has that special ability to make everyone who comes into contact with him feel that he is interested in them, too. It’s an all too rare gift. He has an aura but he also has a kind, welcoming face that says he’s happy to say hello and shake hands. His hands, by the way, are like shovels and could crush coal.

I saw him at The Masters the following year. He was holding court as always on the lawn by the oak tree at the back entrance of the clubhouse. Posing for photographs, pressing flesh, giving the thumbs-up. I waited until the crowd had thinned enough to approach him. I had nothing to say other than “hello” and to remind him that we had played golf together at Bay Hill. He smiled and shook my hand and said “Nice to see you.” I don’t think he had a clue who I was.

Perhaps I should have mentioned The Incident.

*This article was originally published in TGP on 16 September 2015.

Tagged Arnold Palmer